Highlight

Dark Energy Survey scientists release new analysis of how the universe expands

January 22, 2026

- The latest results combined weak lensing and galaxy clustering and incorporated four dark energy probes from a single experiment for the first time.

- Researchers from the Centro de Investigaciones Energéticas, Medioambientales y Tecnológicas (CIEMAT), the Institute of Space Sciences (ICE-CSIC), the Institut de Física d’Altes Energies (IFAE), and the Instituto de Física Teórica (UAM-CSIC) have participated in the scientific analysis of the data.

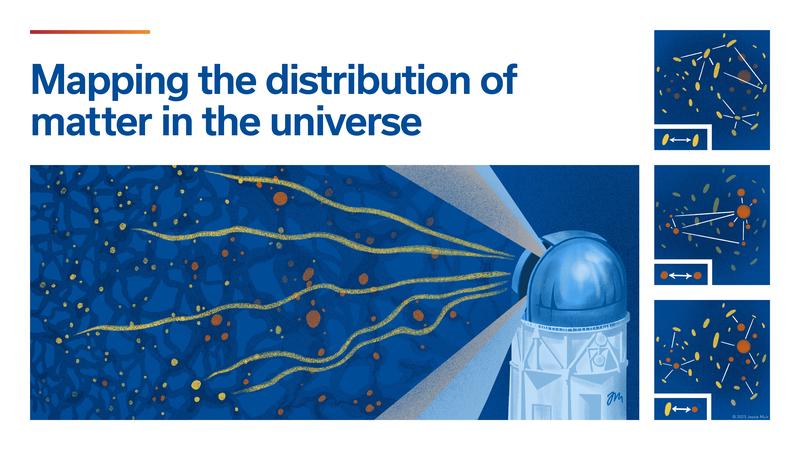

The Dark Energy Survey (DES) collaboration is releasing results that, for the first time, combine all six years of data from weak lensing and galaxy clustering probes. In the paper, which represents a summary of 18 supporting papers, they also present their first results found by combining all four probes — baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO), type-Ia supernovae, galaxy clusters, and weak gravitational lensing — as proposed at the inception of DES 25 years ago.

“DES really showcases how we can use multiple different measurements from the same sky images. I think that’s very powerful,” said Martin Crocce, research associate professor at the Institute for Space Science in Barcelona (ICE-CSIC) and co-coordinator of the analysis. “This is the only time it has been done in the current generation of dark energy experiments.”

The analysis yielded new, tighter constraints that narrow down the possible models for how the universe behaves. These constraints are more than twice as strong as those from past DES analyses, while remaining consistent with previous DES results.

“There’s something very exciting about pulling the different cosmological probes together,” said Chihway Chang, associate professor at the University of Chicago and co-chair of the DES science committee. “It’s quite unique to DES that we have the expertise to do this.”

How to measure dark energy

About a century ago, astronomers noticed that distant galaxies appeared to be moving away from us. In fact, the farther away a galaxy is, the faster it recedes. This provided the first key evidence that the universe is expanding. But since the universe is permeated by gravity, a force that pulls matter together, astronomers expected the expansion would slow down over time.

Then, in 1998, two independent teams of cosmologists used distant supernovae to discover that the universe’s expansion is accelerating rather than slowing. To explain these observations, they proposed a new kind of energy that is responsible for driving the universe’s accelerated expansion: dark energy. Astrophysicists now believe dark energy makes up about 70% of the mass-energy density of the universe. Yet, we still know very little about it. In the following years, scientists began devising experiments to study dark energy, including the Dark Energy Survey. Today, DES is an international collaboration of over 400 astrophysicists and scientists from 35 institutions in seven countries. Led by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, the DES collaboration also includes scientists from Argonne, Lawrence Berkeley and SLAC national laboratories.

To study dark energy, the DES collaboration carried out a deep, wide-area survey of the sky from 2013 to 2019. The DES collaboration built an extremely sensitive 570-megapixel digital camera, DECam, and installed it on the U.S. National Science Foundation Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter telescope at the NSF Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in the Chilean Andes. For 758 nights over six years, the DES collaboration recorded information from 669 million galaxies that are billions of light-years from Earth, covering an eighth of the sky. Spanish institutions have been part of the project since its inception in 2005 and, in addition to making major contributions to the design, construction, testing, and installation of DECam and to data taking, they currently hold important responsibilities in the scientific exploitation of the data.

“From our images, we can measure galaxy shapes and the subtle distortions caused by gravity, as well as the positions of galaxies and how they cluster across the sky. To interpret these measurements, however, we also need to know how far away the galaxies are. In practice, we infer these distances from their colors, measured through observations in different filters.”, says William d’Assignies Doumerg, a doctoral student at the Institut de Física d’Altes Energies (IFAE) and a member of the Dark Energy Survey redshift calibration team.

“In this analysis, we have taken distance calibration to an unprecedented level of precision, allowing us to reliably connect the observed distribution of galaxies with the underlying physics of dark energy,” says Giulia Giannini, co-lead of the DES Redshift Working Group and a researcher at ICE-CSIC in Barcelona

For the latest results, DES scientists greatly advanced methods using weak lensing to robustly reconstruct the distribution of matter in the universe. They did this by measuring the probability of two galaxies being a certain distance apart and the probability that they are also distorted similarly by weak lensing. By reconstructing the matter distribution over 6 billion years of cosmic history, these measurements of weak lensing and galaxy distribution tell scientists how much dark energy and dark matter there is at each moment.

“The final DES lensing measurement includes around 150 million galaxies, an extraordinarily large data set. This is exciting, but it also brings a real responsibility to make sure that every part of the analysis is robust. In DES, we believe we have risen to that challenge. Through new methodologies and strong scientific results, the collaboration has delivered a measurement that will stand as a milestone for many years, and one that we can be genuinely proud of.”, says Simon Samuroff, a postdoctoral researcher at IFAE, who co-led the cosmic shear analysis presented in these results.

In this analysis, DES tested their data against two models of the universe: the currently accepted standard model of cosmology — Lambda cold dark matter (ΛCDM) — in which the dark energy density is constant, and an extended model in which the dark energy density evolves over time — wCDM. DES found that their data mostly aligned with the standard model of cosmology. Their data also fit the evolving dark energy model, but no better than they fit the standard model.

However, one parameter is still off. Based on measurements of the early universe, both the standard and evolving dark energy models predict how matter in the universe clusters at later times — times probed by surveys like DES. In previous analyses, galaxy clustering was found to be different from what was predicted. When DES added the most recent data, that gap widened, but not yet to the point of certainty that the standard model of cosmology is incorrect. The difference persisted even when DES combined their data with those of other experiments. “The Dark Energy Survey is a success story for Spanish cosmology. An entire generation has grown scientifically within DES, and we are ready to lead the next generation of cosmological experiments,” says Santiago Ávila, co-lead of the DES Large-Scale Structure working group, who completed his PhD at the Instituto de Física Teórica (IFT), carried out a postdoctoral stay at the Institut de Física d’Altes Energies (IFAE), and is currently a staff scientist at the Centro de Investigaciones Energéticas, Medioambientales y Tecnológicas (CIEMAT).

Paving the way

Next, DES will combine this work with the most recent constraints from other dark energy experiments to investigate alternative gravity and dark energy models. This analysis is also important because it paves the way for the new NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory, funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, to do similar work with its Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST).

“The measurements will get tighter and tighter in only a few years,” said Anna Porredon, co-lead of the DES Large Scale Structure working group and senior fellow at the Center for Energy, Environmental and Technological Research (CIEMAT) in Madrid. “We have added a significant step in precision, but all these measurements are going to improve much more with new observations from Rubin Observatory and other telescopes. It’s exciting that we will probably have some of the answers about dark energy in the next 10 years.”

The Dark Energy Survey (DES) is an international collaboration of more than 400 scientists from 25 institutions in seven countries, led by Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.

For more information about the project, please visit the experiment’s website: https://www.darkenergysurvey.org/es/

Spain was the first international partner to join the United States in founding the DES project in 2005 and participates through three institutions: two based in Barcelona—the Institute of Space Sciences (ICE-CSIC). and the Institut de Física d’Altes Energies (IFAE)—and one in Madrid, the Centro de Investigaciones Energéticas, Medioambientales y Tecnológicas (CIEMAT), as well as with researchers from the Instituto de Física Teórica (IFT/CSIC-UAM).

- Publication

- Additional Material

- Dark Energy Survey Website

- IFAE Research group

- Observational Cosmology Group

- Contact